Wondering why real maple syrup is so expensive? Here’s a look at the history and process of making real maple syrup and why this delicious goodness worth the cost.

By Virginia George, Contributing Writer

In the Real Food world, we’re used to paying a little more for elements of our food. We often pay a higher price for pastured eggs and chickens, grassfed beef, and uncured pork because it’s more expensive to produce these nutrient dense foods. But have you ever wondered why there’s such a difference in the cost of real maple syrup versus the other stuff in the plastic bottle in the grocery aisle?

I talked a little about the nutritional value of maple syrup at Modern Alternative Kitchen last week. This week I’m going to talk about the history and process of making real maple syrup and why it’s worth the cost.

The Good Stuff

My grandfather sugared his property 20 years ago, and I have memories of riding on the back of the trailer and collecting syrup. He had a wood stove he built outside that he used as an evaporator and I think there are still a couple jars of maple syrup in the crawl space.

A month or so ago my husband suggested that this spring we should try tapping the old maples on the hill ourselves. Since then we’ve spent our time researching the process, digging out my grandpa’s old equipment, and fixing up the wood burning stove. And chopping wood. Lots of wood.

History

No one is sure exactly who discovered that maple sap can be boiled down into syrup. There are some Native American legends and folk stories detailing the discovery of syrup. In one story a man sticks his hatchet into a tree. The next day his wife found a block of ice, or sap from the tree, at the base which she took home to make soup. She cooked it all day and when they ate the soup, it was sweet.

We don’t know for sure how it was discovered, but we do know Native Americans used syrup and maple sugar for trading. Thomas Jefferson even marveled at the maple and transplanted maples to his home in Virginia, only to find out that the temperature there wasn’t conducive to the collection of sap.

From Tree to Table

If you haven’t figured it out already, maple syrup is made from the sap of maple trees. Sap can only be gathered in specific climates during a specific time of year. When the temperature dips below freezing at night and climbs into the mid-40s during the day, the sap “runs.” In the US this typically means parts of New England and the upper midwest during a 6-week window in early spring, beginning approximately March 1.

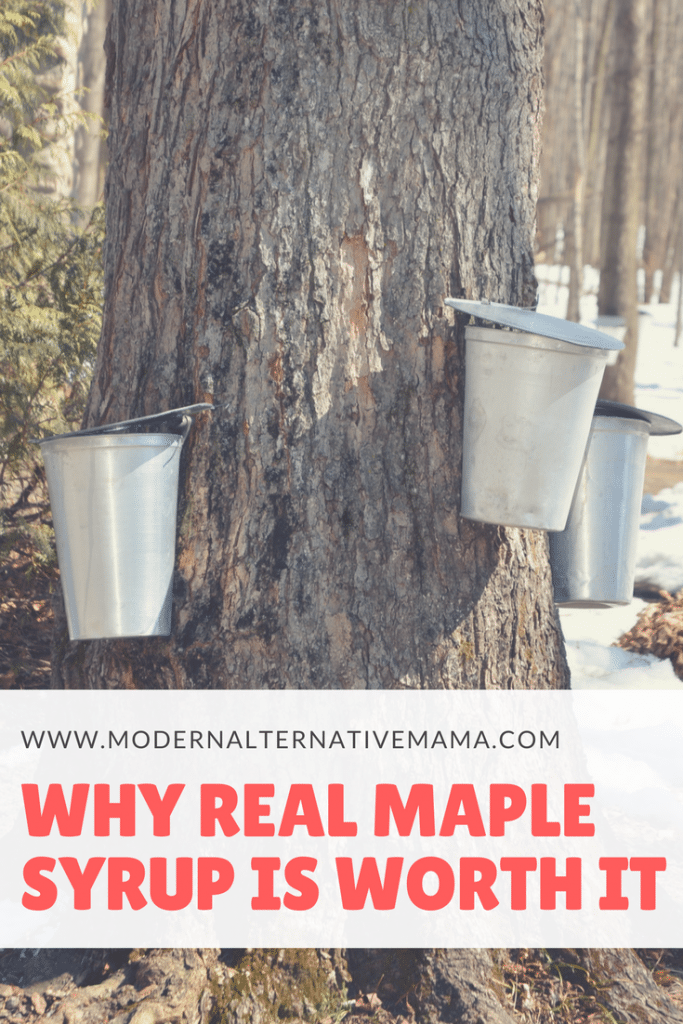

Sap is kind of the lifeblood of the tree. Picture the tree as if it has tons of tiny straws just under the bark all the way around it. The sap runs up and down those tiny straws and brings nutrients to the tree. If a tree that’s too young is tapped it can die. If a large tree has too many taps put into it, it can be harmed as well, so care must be taken to preserve the health of the tree. A general rule is that any tree under 10″ in diameter shouldn’t be tapped.

What is “tapping”? First, a hole is drilled into the tree. Not so deep as to harm the inner wood, but far enough to cut through those little straws. A spike is then gently tapped into the hole and the sap begins to drip into a collection bag or pail. Each day the sap is collected and then boiled down into syrup. The sap to syrup ratio is about 40:1, so it takes 10 gallons of maple sap to make one quart of syrup.

It’s a very labor intensive project. Most of the sap boiling is done outdoors or in a “sugar shack.” We will be using my grandfather’s wood stove outside and then bring it inside to “finish” it. Maple sap is considered syrup when it reaches about 66-67% sugar. The easiest way to determine this is to measure the temperature. At 7*F above the boiling point of water, it is done.

You can then wait for it to cool to about 180*F, pour it into a mason jar, tip it on its side to sterilize the top, and wait for it to seal. It can be stored in the pantry after it seals but should be transferred to the refrigerator after it is opened.

The “Other” Stuff

After all the beautiful history and nostalgia of real maple syrup, it’s difficult to even bring up the “other” stuff. That stuff in the plastic bottle typically has zero actual maple syrup in it. I looked at the ingredients of several varieties on LabelWatch.com and the ingredients are almost unanimously:

Corn Syrup, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Water, Cellulose Gum, Salt, Sodium Benzoate, Sodium Hexametaphosphate, Sorbic Acid, Artificial Maple Flavor, and Caramel Color

And what is “natural butter flavor” anyway? These imitation syrups are a far cry from Real Food. If you can’t afford real syrup or don’t have access to it, I am a huge fan of apple butter on my pancakes in lieu of syrup, or even jam or fresh berries.

Choosing Your Syrup

When you shop for maple syrup you may be confused by the way it’s labeled. Grade A, Grade B, Grade B Amber, what does it all mean? Syrup is graded on its color. Grade A is lightest and has a milder flavor. Grade B is darker and more maple-y. Nutritionally there isn’t a whole lot of difference, but I’ve read that some people prefer to use Grade B because it has a stronger flavor and they can, therefore, use less (and in doing so decrease their sugar intake). Others prefer Grade A for a light maple taste.

Grade is simply a matter of preference. So whatever grade you choose, just make sure it’s the real stuff. It’s nutritionally superior to artificial syrup, it’s a whole food, and it is supremely delicious. The higher price tag is reflective of the amount of work and care that goes into producing it. I know we may have to cut corners somewhere, but seeking out real maple syrup is definitely worth it.

Great post! A few other great maple syrup subs are: honey (straight or mixed with fresh fruit juice or fruit mash), yogurt (straight or sweetened with honey and/or fruit mash, and mascarpone cheese. Yum!

Only real maple syrup in my house! Interesting post

FYI…people make maple syrup all over. Even here in NC. The difference, our winters are a bit less predictable so you have to be on call Jan-Mar for the perfect days.

I didn’t know that sap ran that far south! I read one book that alluded that sugaring only happens on the east coast and Canada, but I know that people in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan do as well. Thanks for sharing!

[…] I have a post going up at Modern Alternative Mama about maple syrup. And the other day I posted at Modern Alternative Kitchen about different […]

I hesitate to buy the Grade A. I’ve read in several places that Grade B or C (the darker ones) are better because they are less processed and lower glycemic. It is so hard to find this in rural Alberta and when I do it’s like $18 a bottle. Ouch! You’d think it would be easier to find in Canada 🙁 Do you have any research showing that Grade A is nutritionally similar to Grades B and C? I’d love to see it and maybe it would help me in my search to acquire healthier and natural sweeteners.

Thanks 🙂

Hi Karen, I’m so sorry I haven’t responded yet. I started to but wanted to make sure I had good information to follow up with you, but I didn’t have time to finish my post. I want to do a quick reply now and I’ll come back with more information later.

In all the research and reading we’ve done about sugaring and making maple syrup I haven’t come across anything that convinces me that any grade is that much more nutritious than another. A lot of things come into play with the grade, but my understanding is that it has a lot to do with the trees and the weather. The earlier sap tends to come out as grade A, and how warm the season is affects syrup grade. There are little things that sugarers can do to improve the flavor of their syrup all around, like being sure to have clean equipment and using a good prefilter to get any sediment out of the sap before it’s boiled down, but those alone don’t determine grade.

Basically grade B isn’t any less processed than grade A, it’s the sap that the trees give you based on the season that the Lord gives you. At least that’s what my husband and I have gathered from our hours of research but I don’t have good links right now. When I get a few minutes in the coming days I’ll try to find some links for either side of the argument.

Thanks so much for your comment, it has given me a lot to think about as we prepare for this project!

[…] succulent goodness from the tree in our own yard. I discussed this a bit in an article I wrote at Modern Alternative Mama, but now I’ll go into more detail with […]

[…] husband and I donned our snowshoes and set off. Sap runs best with temperatures in the 40°s during the day and below freezing at night. The temperature barely […]